Preparing for this post has inspired me to some low-key experimentation. When it came time to assign myself its topic, I landed on the plant genus

Artemisia. This is the genus that, among others, includes the culinary herb tarragon,

Artemisia dracunculus. Which got me thinking that I wasn't sure if I'd ever actually eaten tarragon. I asked Christopher if he was familiar with it; he responded that all he knew about tarragon was that you had to consume it in the 1970s. Without access to a functioning Delorean, I did the next best thing and prepared a dish of tarragon chicken myself. The verdict: very tasty, though I could appreciate why tarragon might have a reputation for being somewhat difficult as it had a light flavour that I could imagine being easily overwhelmed.

Tarragon Artemisia dracunculus, copyright Cillas.

Tarragon is not the only species of

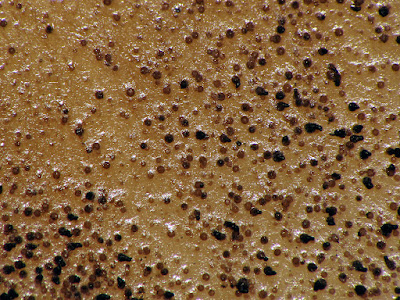

Artemisia of significance to humans. This genus of composite-flowered plants comprsises over five hundred species and subspecies of herbs and small shrubs. The greatest diversity is found in arid and semi-arid regions of the Northern Hemisphere temperate zone (Sanz

et al. 2008). The genus is characterised by its distinctive pollen with surface spinules reduced or absent. This pollen type is associated with the wind pollination typical of the genus, though some species do exhibit features such as sticky pollen and colourful flower-heads associated with insect visitation (Hayat

et al. 2009). The flower-heads or capitula (a reminder that the 'flowers' of composite plants such as daisies and thistles actually represent a fusion of multiple flowers) of

Artemisia are either disciform, with an outer circle of reduced ray florets surrounding the inner disc florets, or discoid, with disc florets only. In disciform capitula, the outer limb of the ray florets is reduced to a membranous vestige, not readily visible without minute examination. The ray florets are female whereas the disc florets are ancestrally hermaphroditic (more on that shortly). In discoid capitula, where the ray florets have been lost, all florets are uniformly hermaphroditic.

Mugwort Artemisia vulgaris, copyright Christian Fischer.

Historically, there has been some variation in the classification of

Artemisia but a popular system divides the genus between five subgenera. A phylogenetic analysis of

Artemisia and related genera by Sanz

et al. (2008) found that the genus as currently recognised is not monophyletic, with a handful of small related genera being embedded within the clade. Time will tell whether this inconsistency is resolved by subdividing

Artemisia or simply rolling in these smaller segregates, but for the purposes of this post they can be simply set aside. The subgenus

Dracunculus, including tarragon and related species, falls in the sister clade to all other

Artemisia. As well as being united by molecular data, members of this clade are distinguished by disciform capitula in which the central disc florets have become functionally male (female organs have been rendered sterile).

Wormwoood Artemisia absinthium, copyright AfroBrazilian.

The second clade encompasses the subgenera

Artemisia and

Absinthium, with disciform capitula, and

Seriphidium and

Tridentatae, with discoid capitula. Not all authors have supported the distinction of

Artemisia and

Absinthium, and Sanz

et al. identify both as non-monophyletic, both to each other and to the discoid subgenera. Because of their similar flower-heads, most authors have presumed a close relationship between the Eurasian

Seriphidium and the North American

Tridentatae (commonly known as sagebrushes). Some have even suggested the former to be ancestral to the latter. However, Sanz

et al.'s results questioned such a relationship, instead placing the

Tridentatae species in a clade that encompassed all the North American representatives of the

Artemisia group.

As well as the aforementioned tarragon, economically significant representatives of

Artemisia include wormwood

A. absinthium, best known these days as the flavouring agent of absinthe (though historically it has also been used for more innocuous concoctions). Mugworts (

A. vulgaris and related species) have also been used for culinary and medicinal purposes. Sagebrushes are a dominant component of the vegetation in much of the Great Basin region of North America, providing crucial habitat for much of the region's wildlife.

Artemisia species have shaped the lives of many of their co-habitants, both animal and human.

REFERENCES

Hayat, M. Q., M. Ashraf, M. A. Khan, T. Mahmood, M. Ahmad & S. Jabeen. 2009. Phylogeny of

Artemisia L.: recent developments.

African Journal of Biotechnology 8 (11): 2423–2428.

Sanz, M., R. Vilatersana, O. Hidalgo, N. Garcia-Jacas, A. Susanna, G. M. Schneeweiss & J. Vallès. 2008. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of floral characters of

Artemisia and allies (Anthemideae, Asteraceae): evidence from nrDNA ETS and ITS sequences.

Taxon 57 (1): 66–78.