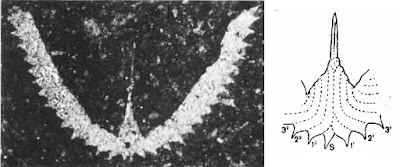

The graptoloid genus Pseudisograptus has been collected from rocks in Australia, North America and eastern Asia dating to the latter part of the Floian stage of the early Ordovician, a bit over 470 million years ago (Cooper & Ni 1986). It is characterised by colonies growing in two branches (stipes) with the stipes spreading outwards and upwards like a pair of wings (indeed, one species of this genus luxuriates in the name of Pseudisograptus angel). In large specimens, the stipes reach about two centimetres in length and about three millimetres wide (from inner margin to the outer apex of the individual thecae). Pseudisograptus species are very similar to, and until 1972 where classified with, species of the related genus Isograptus. They differ, however, in the arrangement and growth of the earliest thecae in the colony. Whereas Isograptus stipes grow outwards immediately from the oldest theca, Pseudisograptus have the first few thecae on each stipes elongated and growing downwards before the stipes makes a later sharp turn upwards. As a result, between the two 'wings' of the stipes there is a more or less distinct triangle (referred to as the manubrium) formed from the bases of the early thecae. At the top of the manubrium is an upright thread, the nema. In a number of graptoloid fossils, an inflated structure has been identified at the top of the nema that probably functioned as a float. I don't know if such a structure has ever been identified in a Pseudisograptus fossil but I imagine it would quite easily be lost in the course of preservation.

Pseudisograptus' disappearance from the fossil record coincides with one of the aforementioned turnovers in graptoloid diversity, the appearance of the biserial graptoloids. These forms, which had two rows of thecae arising from a single central line, rapidly replaced most of the earlier branched forms. The rapid appearance of the biserial graptoloids has made their origins difficult to work out but current thinking is that they arose from a form similar to Pseudisograptus, in which the upward growth of the stipes became steep enough that they met in the middle along the nema. One interesting detail is that two lineages appear to have achieved biseriality at about the same time from closely related but separate ancestors. In the glossograptids, the conjoined stipes met each other side-by-side; in the diplograptids, they met back to back. Pseudisograptus has, at different times, been implicated in the ancestry of both of these groups. Cooper & Ni (1986) regarded Pseudisograptus as paraphyletic and including the direct ancestors of the glossograptids. In contrast, more recent studies by Fortey et al. (2005) and Maletz et al. (2009) have placed Pseudisograptus closer to the diplograptids. These studies have been more agnostic as to whether Pseudisograptus was a direct ancestor or a close relative. If the former is the case then, while the exact Pseudisograptus morphotype would disappear at the end of the Floian, their genetic lineage would continue strong for nearly ninety million more years.

REFERENCES

Cooper, R. A., & Ni Y. 1986. Taxonomy, phylogeny, and variability of Pseudisograptus Beavis. Palaeontology 29 (2): 313–363.

Fortey, R. A., Y. Zhang & C. Mellish. 2005. The relationships of biserial graptolites. Palaeontology 48 (6): 1241–1272.

Maletz, J., J. Carlucci & C. E. Mitchell. 2009. Graptoloid cladistics, taxonomy and phylogeny. Bulletin of Geosciences 84 (1): 7–19.

Do we have any idea why the biserial morphology turned out to be more competitive?

ReplyDeleteGenerally presumed to be more hydrodynamic, I believe.

DeleteThank you

Delete